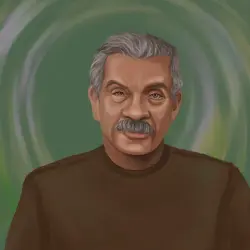

Derek Walcott’s ‘Verandah‘ is a poem about reckoning with colonial history, ancestry, and personal identity. A Nobel Prize in Literature recipient in 1992, Walcott masterfully explores the complex inheritance of a postcolonial Caribbean world. In this poem, he captures the lingering echoes of a fading empire through ghostly figures of the past and the intimate memory of a grandfather, shadows that continue to shape the present and must be confronted to move forward meaningfully. The verandah becomes a liminal space, a threshold where past and present meet. This essay offers a close reading of the poem’s structure, imagery, and historical context, showing how Walcott deals with the ghosts of empire and finds a way to live with what they left behind.

To truly plumb the depths of Derek Walcott's 'Verandah,' the reader should keep a few things in mind. First, it’s important to consider the verandah both as an architectural element and as a symbol. Walcott weaves between both meanings throughout the poem, using the verandah as a threshold between past and present; empire and aftermath; memory and reckoning. Readers should also be attentive to the impact of colonialism - sometimes subtle, sometimes glaring - its systems of oppression disrupted local cultures and shaped personal histories.

Verandah Derek WalcottFrail, ghostly loungers at verandah ends, busher, ramrod colon, your age in ashes, its coherence gone,planters whose tears were marketable gum, whose voices scratch the twilight like dry fronds gilt with reflection,middlemen, usurers whose art kept an empire in the red, colonels hard as the commonwealth’s greenheart, (...)

Summary

In ‘Verandah,’ Walcott comes to terms with the complicated legacy of colonialism in his native St. Lucia by reflecting on his family history. The poem is an elegy that honors and queries his ancestors, exploring the influence of the past on the present day.

This poem is a meditation on colonial decline and personal inheritance, blending historical reflection with personal musings. The poem opens with images of frail colonial men fading on the verandah, symbolizing liminality and twilight. It moves through vivid metaphors and ironies to portray them as “bully-boys” economically, culturally, and morally. Phrases like “planters whose tears were marketable gum” and “colonels hard as greenheart” expose the exploitative foundations of empires.

Walcott’s focus narrows from the larger empire to his specific ancestry. His grandfather emerges as a complex personal and symbolic figure, whose legacy must be confronted and interpreted by his descendants. This legacy is captured through fiery imagery and metaphors. The striking image of a “Roman end” by fire and the burial of “charred, blackened bones” in a child’s coffin conveys the tragic, self-consuming end of imperial grandeur, reduced in stature and buried on a “strange coast.”

Yet the poem doesn’t remain in lament. Through metaphors of regeneration (“blackened timber with green little lives”) and destructive pressure converted to beauty and value (“sparks” becoming “stars” and “diamonds out of coal”), Walcott suggests a future forged in perseverance and love.

The poem takes the reader on a journey of understanding: from detached observation to grief, and finally, to reconciliation. The speaker climbs the ancestral stairs with a “darkening hand,” reaching toward “frail, mute friends” who represent both the dead colonials and the silent familial past.

In its final lines, ‘Verandah‘ offers the earth as “shrine and pardoner,” a resting place that absorbs grandeur and guilt alike. The return to the image of “ghostly loungers at verandah ends” brings the poem full circle, tying personal legacy to colonial history.

Expert Commentary

Historical Context

This poem is set against the historical and cultural realities of postcolonial Saint Lucia, an island in the Caribbean, where Walcott was born and raised. Written in the 20th century, the poem reflects a period of transition and reckoning among nations that had faced centuries of European colonization (the British in this specific case) as they were moving towards political independence and self-definition.

Through personal memory and historical reflection, the poem explores the lingering presence of colonial influence and the legacy it left behind. The verandah, an architectural element of colonial houses where the British lived in India, Africa, and the Caribbean, became absorbed into the local cultural landscape. It becomes a symbol of liminality, representing a space between inside and outside, past and present, tradition and change. This indeterminacy of a space adjoining defined areas and a site of dramatic change serves as a metaphor for the Caribbean identity, shaped by a mix of African, European, and indigenous cultures.

British colonial ventures in Asia, Africa, and the Caribbean were known for extensive resource exploitation and a disregard for indigenous cultures. Driven by economic aims, colonizers extracted significant wealth in materials and labor, often through force, to benefit Britain at the expense of local populations. This economic control frequently involved deliberately suppressing native languages, customs, and governance, replaced by European models. The lasting impact included cultural loss, social instability, and persistent economic inequalities as significant legacies of colonial rule.

The “burning house” metaphor in the poem describes the destruction of these colonial institutions that facilitated the Empire’s domination and the scars resulting from the collapse. This collapse makes way for new beginnings, but also calls for reckoning with its influence. Walcott deals with the intergenerational impact of colonialism and the struggle to reconcile a painful past with a meaningful and dignifying future.

Born of mixed African and European ancestry, Walcott inherited the very contradictions he writes about; his English colonialist grandfather married a local black woman. His work often engages with the tension between these legacies. The elegiac tone and references to ancestors and inheritance show a poet addressing his cultural legacy, racial hybridity, and the search for selfhood in a postcolonial Caribbean world.

Structure and Form

‘Verandah‘ is structured as a 14-stanza free verse poem, with no consistent meter or rhyme scheme. This lack of formal constraint mirrors the fluidity of memory and thought, allowing Walcott to shift seamlessly between past and present and between personal meditation and detached historical reflection.

The three-line tercet stanzas are compact and reflective in mood. Their brevity gives the poem a fragmentary feel – like entries in a journal, moving through clear impressions and dreams, mirroring how memory surfaces in patches rather than unfolding in a continuous narrative. Walcott uses enjambment to enhance this sense of uncontainment, creating a flowing continuity that links the poem.

The poem has a cyclical structure, beginning and ending on the verandah (the first and last lines are nearly identical). This circular framing underscores the poem’s meditation on inheritance, as the speaker makes a complete journey: distancing himself from his ancestors to question their moral limitations, then arriving at a reluctant acceptance of how deeply their legacy shapes his own life.

Literary Devices

Walcott uses several literary devices to create an elegiac mood, change tones, and carry images of solemn mourning and frank reflection in the poem, ‘Verandah‘:

- Walcott uses enjambment extensively through the poem, with lines spilling into the next (as in stanza two) and sometimes even into another stanza (between stanzas eleven and twelve). This gives the poem a fluid momentum, mirroring how memory and thoughts escape containment. As such, the poem appears less formal and more intimate. Walcott also uses this device to slip seamlessly between personal memory and detached historical reflection.

- Metaphors carry significant weight in ‘Verandah‘, and Walcott uses several to explore memory, identity, and history in the poem. The verandah itself is the central metaphor: a feature of colonial architecture that marked the border between the house and the outdoors. It comes to mean a threshold between generations and cultures; a stage where ghosts of history gather and meet with the living.

- Walcott uses symbolism in a layered, nuanced way to weave together a network of interconnected ideas, rather than presenting a straightforward allegory. Symbols like the burning house represent the collapse of colonial structures and the destruction they brought to the lands they occupied. The verandah symbolizes a liminal space, a threshold connecting two phases: past and present, colonial and postcolonial, personal memory and collective history.

Detailed Analysis, Stanza by Stanza

Epigraph

Only a pure and virtuous soul

Like a seasoned timber, never gives,

But, though the whole world turn to coal,

Then, chiefly lives.

– Herbert

‘Verandah‘ opens with an epigrammatic quote from the poem ‘Virtue‘ from George Herbert. Herbert’s lines affirm an ideal: that virtue, like seasoned timber, is inherently resilient: unchanging, even in the face of devastation. In contrast, Walcott’s poem invokes this imagery not to suggest innate purity, but to explore how endurance and moral clarity can emerge after crisis. Throughout ‘Verandah,’ symbolism of fire, timber, and regrowth is repurposed to reflect a journey through moral ambiguity. Here, virtue is not a given, but something forged through honest confrontation with a fractured, colonial past. In Walcott’s hands, the soul “chiefly lives” not because it was always pure, but because it has faced its contradictions and chosen renewal.

Stanza One

Frail, ghostly loungers at verandah ends,

busher, ramrod colon,

your age in ashes, its coherence gone,

Walcott opens the poem with an image of old colonists as “frail loungers at verandah ends.” The verandah is an architectural element introduced by the colonists, and being a sort of porch, symbolizes the space between the house proper and the outdoors. This ushers in the idea of an age in its twilight.

The “loungers” themselves are an example of double entendre, referring to sun lounger chairs as well as old colonists. They lounge around, profiting from the hard work and suffering of those they oppress in their own country.

“Busher” may be referring to the colonisers as amateurs, as it is often used to refer to the inexperienced or unskilled. However, it may also be a pun on the location name of Bushehr, which was also occupied by the British three separate times. The British failure to maintain this occupation perhaps reflects their “amateur” attempts at colonisation. As such, the speaker is disparaging the colonisers through direct address.

The phrase “ramrod colon” is another clever pun. As a reference to the body part, it evokes the image of the stiff spine characteristic of a military posture, but also a rigid, inflexible, and somewhat pompous nature. Colon also could refer to “colonist” or “colonizer”, yet invokes an insulting tone as it refers to the body part.

Line 3 suggests an age in decline: its ideals, values, and institutions dead or losing meaning. The imagery presents a vivid sense of age, stiffness, decay, and a thing nearing its end. Through Walcott’s use of direct address, anger is imbued in this line as he confronts the colonisers, warning them of their end.

Stanza Two

planters whose tears were marketable gum, whose voices

scratch the twilight like dry fronds

gilt with reflection,

The “planters” and their sorrow, expressed through their “tears of marketable gum”, are seen as commodified and artificial – produced mainly for profit or effect. Their tears are rendered metaphorically as the milky-white resin that drops from trees tapped for rubber. This was one of the primary exports for Caribbean planters. The parallel between the planters and the rubber trees is undeniable: used and drained for the profit of others. This emphasises the dehumanising effect colonisation had on the people of Saint Lucia.

Their “voices scratch the twilight like dry fronds,” a simile comparing the sound of their speech to the harsh rustling sound of dry palm leaves. The twilight suggests the fading era, and “gilt with reflection” adds a touch of the superficial grandeur that replaced something once golden. These old men try to project an image of past glory in a failing voice.

Stanza Three

middlemen, usurers whose art

kept an empire in the red,

colonels hard as the commonwealth’s greenheart,

The old men are shown to be economic agents of the Imperial empire, its figures of commerce and finance, who benefit from the Empire’s exploitative economies.

Their activities “kept the empire in the red”, which is an example of double entendre: either in debt, as a negative balance is “in the red”, or a metaphor highlighting that they are bloodstained in the violence of Empire. Their profit is made through the pain and suffering of others. Consistent with the poem’s theme, it is more likely that this illustrates a moral debt rather than an economic debt.

These men are as hard as “the commonwealth’s greenheart,” which is a simile, likening them to a tough, dense, and durable wood native to the Caribbean, known as greenheart. This stanza describes the role of these men in the oppressive and extractive nature of colonial rule.

Stanza Four

upholders of Victoria’s china seas

(…)

roarers at the white Empire club,

The “upholders” refers to supporters of the reign of Queen Victoria, and “Victoria’s china seas” is a metaphor for the vast, global reach of the British Empire. This is imagined daintily as metaphorical scenes designed on porcelain – “lapping embossed around a drinking mug”, a visual image that trivializes imperial grandeur.

“Bully-boy roarers” describes the loud and aggressive colonial men: members of the exclusive and racially segregated social elite. The plosive “b” alliterates and the repeated “r” sounds accentuate these men’s harsh, aggressive nature, as they benefited from and boasted about the colonial institutions that dominated the colonies.

Stanza Five

gone all your gold and scarlet jubilees,

(…)

round the last post,

This stanza continues with its herald of the end of an age. “Gold and scarlet” refers to colors of royalty, wealth, and power, and “jubilees” to significant anniversaries; together, they paint a picture of high pomp. However, these colours combined with jubilees signify different anniversaries associated with monarchies. The “gold” jubilee marks fifty years, whereas “scarlet” likely refers to a ruby jubilee, which marks forty years. Once again, Walcott adopts a mocking tone as he highlights the inability of the British Empire to successfully maintain a colony.

“Tarantara” is an onomatopoeia for the bugle call at military occasions. Like a “sunset,” the end of empire is furled metaphorically like a flag is rolled. “[R]ound the last post” refers to the bugle call at the end of the day, which is also played at military funerals to lay a soldier to rest.

Stanza Six

‘the flamingo colours’ of

(…)

Rooted from some green English shire,

The first line of this stanza uses the image of the bright plumage of a flamingo to represent something once vibrant but now losing its brilliance. Here, it refers to the “fading world” that is the British Empire in its decline. At this point, a volta sees the tone shift from a detached observer of the larger British Empire and its immense global impact to a personal, elegiac one addressed to his grandfather’s ghost, through apostrophe. This switch creates a powerful sense of immediacy and sharpens the effect of the following stanzas.

“[M]y grandfather’s ghost” continues in the vein of a dying and evanescent world. The guttural alliteration of this line communicates Walcott’s sadness and grief, acknowledging that his grandfather is fading into the distant past.

“Rooted from some green English shire” alludes to the ancestral roots of his father from some rural English town with its green landscapes. This line features a wealth of sibilance, emphasising the distance between Walcott and this unknown “shire”.

Stanza Seven

you sought a Roman

(…)

gathered your charred, blackened bones,

The first line of this stanza breaks off at “Roman,” and the next begins with “end” – a sharp dislocation of the senses. This enjambment impactfully illustrates the sense of destruction left in the wake of the Empire’s colonisation, one that ends up engulfing itself. As if to buttress this idea, the third line runs the length of the first two lines and forms a complete idea. In this, the grandfather’s biracial son “gathered” – trying to make a fresh coherence and new meaning out of the desolation caused by his forefathers – “charred, blackened bones”. The plosive alliteration of the latter two words emphasise the brutality of the death marked by the bones.

This line also provides gruesome visual imagery of the devastating and horrific fallout of suicide and death by fire. This is due to the “Roman end” alluding to a symbolic suicide tradition practiced among Roman nobles, like Seneca and Cato to maintain honor, avoid capture, or defy their enemies. Walcott joins with this the motif symbol of fire as the agent of destruction in this poem.

Walcott’s grandfather was a colonialist who married a local Caribbean woman; this poem addresses the poet’s mixed heritage as one of his grandfather’s legacies. There is no historical record of Walcott’s grandfather dying by suicide, by fire, or otherwise, so the image is almost certainly symbolic. Walcott invokes him not just as an individual but as an embodiment of the British Empire’s decline: an imperial figure whose end is tragic and self-consuming and leaves devastation in its wake. Like the colonies left behind, the “mixed son” must gather the “charred, blackened bones” of that legacy and make sense of a new future from its remains.

Stanza Eight

in a child’s coffin, sire,

(…)

Why do I raise you up? Because

The alliterative “child’s coffin” in the first line suggests something small and vulnerable, completely at odds with “sire”: a formal, respectful term used to address a king or dignified figure with power. The juxtaposition of the grand title with a diminishing container creates a sharp contrast, laced with irony. What was once a towering figure – “colonels hard as greenheart,” “upholders of Victoria’s china seas” – now rests in a box meant for a child. Likewise, the imperial grandeur has lost stature and is now shrunk.

“Buried them himself” suggests that burial was personal and solitary, rather than a social event. It took place on “a strange coast,” evoking a sense of exile and reinforcing the theme of the grandfather’s uprootedness. The privacy of the burial also hints at something deeper, perhaps something done in secrecy, or out of shame. It may represent the son’s unwillingness to reckon with the past or confront the full horror of what has been inherited. For the grandson, Walcott himself, this silence is unacceptable. He respects his grandfather despite his troubling legacy. Walcott prepares to explain why he feels this way, posing a rhetorical question while addressing his grandfather directly through apostrophe.

Stanza Nine

your house has voices, even your

(…)

your genealogical rooftree survives

In stanza nine, the grandfather’s house is personified as crying, its walls imbued with grief and not just memory. This sorrowful voice represents the weight of unspoken histories and the emotional aftermath of colonial decline. The “unguessed, lovely inheritors” are the unforeseen descendants (perhaps biracial children) whom the grandfather could not have imagined, but who now bear the legacy of his life. Even the “burnt house,” likely a metaphor for personal destruction and imperial collapse, supports the surviving “genealogical rooftree,” a metaphor for family lineage. The lineage endures despite the “charred, blackened bones,” life goes on: unexpected, mixed, and transformed.

Stanza Ten

like blackened timber with

(…)

in that sea-crossing, steam

Walcott makes a transition from charred bones that get buried to “blackened timber with / green,” a simile that suggests rejuvenation after fire, like trees stripped by a brush fire sprouting fresh shoots (“green, little lives”) from which life begins again. This image extends the metaphor of the rooftree mentioned in the previous stanza.

“Ripen for” is a metaphor which suggests the speaker is coming into his own as his grandfather approaches his “twilight,” a metaphor for the ending of an era and the ending of a life.

Here, he seems to be coming to terms with the complexities of the past. The sibilant consonance of “sea-crossing, steam” once again emphasises distance, as Walcott refers to the voyage from England that uprooted his grandfather: part of the colonial venture and its exploitative history. It may also allude to the earlier transatlantic slave trade, which displaced the Caribbean peoples in the first place and left deep scars across their cultural memory, which the colonial episode exacerbated. This duality reflects the interwoven legacies that shaped the Caribbean identity, and by extension, Walcott’s own identity.

Stanza Eleven

towards that ancestral, vaporous world whose souls

(…)

because

The “ancestral vaporous world” likely refers to an imagined ancestral land: intangible, dreamlike, and possibly linked to the dream mentioned in the previous stanza. Its sibilant consonance adds to this sense of ethereality, while reinforcing the distance once again. It cannot be England – a real, historical place and the home of the oppressor, not the oppressed.

“[L]ike pressured trees bring diamonds out of coal” is a simile that evokes the natural formation of diamonds: dead trees, buried and subjected to immense heat and pressure, transform first into coal, then into diamonds – symbols of purity, strength, and high value. Walcott uses this image to suggest that Caribbean postcolonial identity, though forged in suffering and trauma, may yield something resilient and precious.

Stanza Twelve

those sparks pitched from

(…)

love you suffered makes amends

The first line in this stanza is introduced by the final line of stanza eleven – “because” – reinforcing how coal transforms into diamond through pressure. Here, Walcott asserts that the “sparks” (a metaphor perhaps referring to the grandfather’s lineage or legacy), which fly out of the “burning house,” a metaphor for the destruction of colonialism, are stars: like diamonds, they become beautiful, enduring, and valuable through adversity.

The second line continues the poem’s tone of reverent reconciliation. Walcott acknowledges that, whatever his grandfather was, he was someone his father admired deeply and someone who shaped his father. The phrase “love you suffered” in the third line is oxymoronic, capturing the complex pain woven into deep affection. Though bitter, it suggests that the hardships endured for love ultimately lead to healing, recompense, and this love is what reconciles him to his grandfather, despite what he represents.

Stanza Thirteen

within them, father. I climb

(…)

frail, mute friends

“Within them, father” links back to the love that redeems or makes amends in the previous stanza, and shows how Walcott uses enjambment to spill thought into the succeeding lines and stanzas. The “sparks” or “stars,” those positive outcomes, balance out the pain his father endured.

“I climb up your stair, / I stretch a darkening hand” is symbolic of the speaker approaching, now with understanding and emotional maturity, his ancestral past. It suggests a metaphorical ascent into that legacy. The “darkening hand” may evoke both evening and racial identity, deepening the symbolism.

“[T]hose frail, mute friends” recalls the old colonials lounging on the verandah, or may even refer to the speaker’s family lineage. Now they are mute, no longer possessing the brittle voice that once scratched like “dry fronds” (as in the second stanza). The colonial legacy has gone quiet now that the speaker has addressed and come to terms with it.

Stanza Fourteen

who share with you your l

(…)

loungers at verandah ends.

The idea of the earth as a “last inheritance” alludes to death and burial, suggesting it as our universal fate. As the final resting place, the earth becomes sacred (“shrine”) and also a “pardoner” in the sense that, in death, past sins are forgiven or quietly dissolve. This framing of death is gentle, offering both closure and absolution.

The final line circles back to the poem’s opening, completing an elegiac loop. The loungers return, now “shy and ghostly,” evoking the spirits or lingering memories of the dead, still haunting the familiar space of the “verandah.” Though they are no longer fully present, their presence is still felt.

FAQs

The poem’s central theme revolves around the legacy of colonialism and its impact on Caribbean identity and history. It explores the fading world of the British Empire, the presence of ancestral ghosts, and the speaker’s negotiation of his own mixed heritage within this complex past. Also addressed are themes of memory, death, and transition.

A verandah is a roofed, open-air structure attached to a building, providing an extended outdoor living space. Originally from India, British colonialists adopted and adapted this architectural feature, bringing the term (from Hindi “baranda”) and the design to other parts of their empire, including Australia, Africa, and the Caribbean. The verandah became a distinctive colonial architecture element, serving practical climatic needs and signifying a particular lifestyle.

The “verandah” is a potent liminal or transitional space symbol. It is neither fully inside nor entirely outside the “burnt house” (representing the postcolonial Caribbean). Walcott uses it to address the in-between state of Caribbean identity, between European and African influences, and the ongoing dialogue between past and present.

The poem begins with a detached, almost ironic tone as it describes the decline of colonial figures and their fading world. But as the speaker turns to his grandfather and father, the tone shifts, becoming more personal, reflective, and mournful. In the final stanzas, there’s a sense of quiet searching as the speaker tries to understand what his forebears left behind and what it means for who he is now.