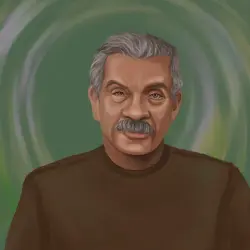

This poem is the final section of the long poem ‘The Schooner Flight’, which featured in Derek Walcott’s 1979 poetry collection, ‘The Star-Apple Kingdom’. This particular section is a reflection on identity and exile that echoes the poet’s own experience as a man of mixed heritage from the Caribbean.

The poem captures the thoughts of the schooner captain Shabine, a self-described “red nigger” who feels adrift between cultures. Following a violent storm, which serves as a metaphor for the turmoil of his life, Shabine attempts to resolve his sense of displacement and his search for a place to belong. Through his voice, Walcott explores the themes of cultural isolation and the search for an ideal home. He ultimately finds that true belonging may lie not in a physical location but within oneself.

A few tips to help with reading this poem: First, pay attention to Walcott’s use of dialect, which gives the poem a raw, grounded authenticity that draws you closer to Shabine’s voice. The political and social weight of postcolonial Caribbean life runs just beneath the surface, and it’s part of what animates the poem’s emotional core. Also, take note of Walcott’s layered literary devices and the rich maritime imagery—hallmarks of his style and connected to the geography and psyche of the Caribbean.

The Schooner Flight, Section 11: After the Storm Derek WalcottThere’s a fresh light that follows a storm while the whole sea still havoc; in its bright wake I saw the veiled face of Maria Concepcion marrying the ocean, then drifting away in the widening lace of her bridal train with white gulls her bridesmaids, till she was gone. I wanted nothing after that day. Across my own face, like the face of the sun, a light rain was falling, with the sea calm. (...)

Summary

‘The Schooner Flight, Section 11: After the Storm‘ is the personal reflection of a schooner captain, Shabine, after surviving a treacherous storm at sea. His thoughts turn to his life and identity as a mixed-race Caribbean man, and his self-imposed exile to distance himself from the postcolonial society he finds disillusioning.

After the storm, Shabine finds himself in a state of calm, both literally and figuratively. The brutal tempest, which represented the tumultuous challenges of his life, has passed, leaving him with a sense of clarity. The poem uses the imagery of the sea and the schooner’s journey as a metaphor for Shabine’s voyage through life. In the earlier parts of the poem, we find that he is a “red nigger” who feels like an outcast, not fully belonging to either his African or European heritage: an in-between feeling that subtly animates this poem.

Shabine’s journey is a quest for a place where he can feel a sense of belonging. He has left his home and his wife, believing that he can find a new identity or purpose at sea. However, he realizes that no matter how far he travels, his past and his identity are inseparable from him. The poem concludes with accepting his fate with all its baggage, who finds home and reconciliation with himself while roaming the seas (“My first friend was the sea. Now, is my last”).

Expert Commentary

Historical Context

‘After the Storm‘ is the eleventh and final section of Derek Walcott’s long poem, ‘The Schooner Flight‘. Its background is a turbulent chapter in Caribbean history. Many nations had only recently shed colonial rule. Trinidad and Tobago, Shabine’s home, gained independence in 1962, but the high hopes that came with independence were already fraying. The Black Power Revolution of 1970 in Trinidad exposed the depth of that fracture: a mass uprising against Prime Minister Eric Williams’s government. It was driven by the belief that independence had left economic power in the hands of a white and foreign elite, which deepened economic and social inequalities of colonial rule. The protests and a sympathetic military mutiny were met with a swift suppression by the government. This poem takes place against the backdrop of the resultant public disillusionment, evident by Shabine’s bitter reflections on “corruption”, which become more poignant with historical context. His flight is as much an escape from political rot as personal entanglements.

The nation-building project itself was fraught. These islands had to fashion a shared identity out of the colonial inheritance: peoples of African, Indian, and European descent alongside indigenous survivors, all bound by languages and systems designed by former rulers. Shabine – whose very name in a Caribbean context means a person of mixed race, and who calls himself a “red nigger” of African, Dutch, and English blood – embodies this hybrid reality. His assertion, “either I’m nobody, or I’m a nation,” distills the postcolonial identity crisis into a single, defiant paradox. His voice, mixing standard English with Caribbean Creole, mirrors Walcott’s own navigation of inherited forms, asserting a rhythm and worldview rooted in local soil.

Shabine is not an outright heroic patriot. He is, after all, a salvage diver running illicit smuggling operations for the very officials presiding over the decay he condemns. His livelihood reflects how failed states breed underground economies, where survival often depends on bending or breaking the law.

Walcott frames Shabine’s journey by drawing on a rich literary tradition. ‘The Schooner Flight‘ echoes classic epic sea voyages: Homer‘s ‘Odyssey‘ and Coleridge’s ‘The Rime of the Ancient Mariner‘. Yet unlike Odysseus, who longs for home, or the Mariner, who seeks redemption for a sin against nature, Shabine’s quest is for inner peace and a sense of belonging.

Structure and Form

This poem does not follow a rhyme scheme or metrical pattern. It is presented as a continuous block of free verse, devoid of formal stanza breaks. This unbroken visual form powerfully reinforces the poem’s central theme of an ongoing journey and Shabine’s continuous stream of consciousness. The lack of traditional stanzas allows thematic shifts to unfold organically, mimicking the seamless flow of both the sea voyage and deep introspection. This continuous presentation enhances the poem’s intimate and direct tone, inviting the reader into Shabine’s uninterrupted monologue.

The interplay of enjambment and caesura dictates the poem’s unique rhythm and pace within the free verse structure. Enjambment allows lines to flow uninterrupted, creating a sense of continuous thought and narrative momentum that mirrors the sea voyage and Shabine’s reflections. This fluid movement prevents a choppy reading and establishes a more organic, conversational feel.

Conversely, caesuras introduce deliberate pauses within lines, serving as structural punctuation that controls the reader’s pace and emphasizes specific words or shifts in thought. This unbroken flow and precise interruption effectively mimics natural speech patterns and internal deliberation, making the poem’s form reflective of its theme of an ongoing journey of physical passage and introspective processing.

Literary Devices

This is a beautiful and reflective piece that uses the speaker’s voyage aboard a schooner to explore his pursuit of home and purpose in a topsy-turvy world. Walcott uses several literary devices to address this:

- Imagery is the most dominant literary device, creating the most evocative impressions. Visual imagery is used to capture the sea’s turbulence in phrases like “sea still havoc,” and the schooner’s bowsprit, in its driven purpose, is presented as an “arrow” and a “lunging heart” in an imagery-heavy metaphor.

- Walcott uses brilliant and fresh metaphors to present ideas about the sea in new ways. He compares the ocean’s white foam to the “widening lace of her bridal train,” which also personifies the ocean itself. Walcott also introduces the concept of how the sea and sky seem to meet in the horizon as two pieces of fabric sewn together with one seam.

- He frequently uses Caribbean dialect in the poem, a literary device known as vernacular, which lends authenticity to the speaker’s voice and identity. He uses “just press,” a common Caribbean English phrasing for “just pressed,” and “cotching” which means “perched” in Caribbean English.

Detailed Analysis

Lines 1-6

There’s a fresh light that follows a storm

while the whole sea still havoc; in its bright wake

I saw the veiled face of Maria Concepcion

marrying the ocean, then drifting away

in the widening lace of her bridal train

with white gulls her bridesmaids, till she was gone.

This section preceding this poem, ‘Section 10: Out of the Depths‘, describes a violent and life-threatening storm that the protagonist, Shabine, and his schooner endure. It’s a period of intense struggle, fear, and even a confrontation with mortality; in the midst of this storm, Shabine considers his faith and survival. ‘After the Storm‘ describes a “fresh light” that appears after the skies settle, even while the “whole sea still havoc.” The word “havoc” is cacophonous, reflecting the harshness of the storm. This creates a strong contrast between beauty and destruction.

The sea is personified, characterised as Maria Concepcion’s groom. Maria Concepcion is Shabine’s lover, whom he had left behind: throughout the poem, he experiences much internal conflict over this abandonment.

The name “Maria Concepcion” is a clever allusion crafted by Walcott. It alludes to Mary of the Immaculate Conception from the Holy Bible: Walcott chooses a holy name for a humanly flawed character to highlight the difference between ideals and real life. Maria’s symbolic departure, “drifting away”, does help Shabine find a kind of spiritual resolution and new beginning.

A beautifully worded metaphor can be found in the “widening lace of her bridal train”, which represents the foam on the sea. This contributes to the extended metaphor of a marriage, which is furthered by the “white gulls her bridesmaids”, which anthropomorphises the gulls that fly above the sea, resembling a bride’s attendants as the image of Maria disappears into the sea.

Lines 7-9

I wanted nothing after that day.

Across my own face, like the face of the sun,

a light rain was falling, with the sea calm.

Line 7 is markedly shorter than those before it. The reduced number of syllables conveys a deep sense of finality or profound impact on the speaker, which reflects the line’s contents. Shabine expresses a complete lack of desire for anything else life may offer after experiencing profound heartbreak. The tone here becomes sombre and sincere as Shabine shares his personal reflections.

In line 9, the serenity that overcomes Shabine is reflected in the sudden calmness of the waters. This symbolises the inner peace that he has found during the storm. The parallel between Shabine and nature is strengthened, as he compares his face to that of the sun in a simile. Through this, the sun is also anthropomorphised, as its attribution of a “face” and comparison to Shabine give it a human quality. This perhaps suggests that Shabine no longer feels alone.

Lines 10-17

Fall gently, rain, on the sea’s upturned face

(…)

is clothes enough for my nakedness.

From lines 10-17, Walcott uses an extended metaphor of bathing and clothing to explore themes of renewal and spiritual liberation. Walcott uses apostrophe to address the rain, imploring it to “[f]all gently” on the sea. The recurring ‘f’ alliterates and sibilant consonance of line 10 bespeaks a soft expression.

The personified sea, with its “upturned face,” is likened to a girl showering through a simile, creating a hopeful image of renewal for the islands, a poetic prayer for a future as good as “Shabine once knew them”. This evokes a tender imagery and suggests that Shabine is now looking back at the islands with love.

The central metaphor hinges on this prayer. When Shabine declares, “I finish dream,” it signifies a profound shift from active hope to being at spiritual ease. He’s not abandoning his people or their struggles, but shedding his burden and anxieties. His new “nakedness” isn’t a lack of identity, but the embrace of being one with nature.

Another extended metaphor begins as the world is compared to laundry, seemingly triggered by the olfactory imagery of the sea smelling like the ironing of clothes, as the sun beats down on it for the first time since the storm. The reader can feel the heavy humidity in the air with this masterful line.

The laundry metaphor, coupled with the visual parallelism of “the rain wash and the sun iron”, results in “white clouds, the sea and sky with one seam.” Through this, the clouds become puffs of steam from an iron, as the sea and sky become two pieces of connected fabric. The “one seam” that unites them symbolises their interconnectedness.

This unified image becomes “clothes enough for my nakedness,” representing Shabine’s new purified, natural worldview. This new “clothing” frees him from his concerns with the flaws of his society. In this moment of imaginative release, Shabine experiences an enlightenment that allows him to find peace, freed from the hatred and disappointment of his country’s political history.

Lines 18-21

Though my Flight never pass the incoming tide

(…)

if my hand gave voice to one people’s grief.

This section runs on in a long enjambment, giving the impression of a stretch of smooth sailing. Lines 18 and 19 suggest that Shabine’s physical journey does not take him beyond the boundary of his native Caribbean region (“of the final Bahamas”).

“Flight” here is a double entendre: the literal name of his vessel and his metaphorical escape. This implies that Shabine’s quest for identity does not entail escaping his origins but finding meaning within them, a recurrent theme in Walcott’s work.

“[L]oud reefs” create strong auditory imagery, giving sound to something which was once silent. The “Inland sea” and “final Bahamas” are metaphors for Shabine’s personal limits: though he has been unable to bypass them, there is a sense of contentedness in his progress, underlined by his self-proclaimed state of being “satisfied”.

The repetition of consonant sounds – such as the fricative “f” sound in “Flight” and “final” and the repeated “l” sound in “loud” and “inland” – create an easy, relaxed tone, emphasizing Shabine’s newly found inner peace.

His satisfaction is chiefly in having found his purpose as a poet: in his “hand” giving “voice to one people’s grief,” or more precisely, to the collective suffering and historical pain of the Caribbean people. “Hand” and “voice” are synecdoches for the poet and his work.

Lines 22-29

Open the map. More islands there, man,

(…)

to the roofs below; I have only one theme:

In the tone bespeaking a rush of boundless and excited affection, Shabine eagerly issues the imperative “Open the map”. His relaxed yet excitable demeanour is underscored by his use of colloquialisms, such as “man”. This gives these lines a more intimate and authentic regional voice, showing his bona fides as a Caribbean.

He appreciates the sheer number, which he compares to “peas on a tin plate” in a metaphor. In an apparent hyperbole, he refers to there being “one thousand in the Bahamas alone”, which exceeds the actual number (though they are still numerous in reality). The vast variety in size and geography of the islands in the Caribbean is emphasised through the juxtaposition of “mountains” with “low scrub”.

From his position at the “bowspirit”, he performs a kind of spiritual benediction over the communities he sees. The details he observes – such as the “blue smell of smoke in hills” and the “one small road winding down” – are signs of human habitation seen closely, from a personal view rather than a detached perspective.

Visual imagery is used to describe the cozy setting of the human habitation. The small winding road is compared to a twine in a simile. Walcott uses domestic images to show Shabine’s intimacy with the islands. They are not just landmasses, but places filled with life and people he feels a deep kinship with.

Synesthesia, which represents a specific sensory experience in terms of another one, is used with the expression “the blue smell”. Blue, usually associated with sight, is defined in terms of smell, an expression that instantly pulls the smoke from the distance of vision to within olfactory range. This adds to the mystical feel of Shabine’s state.

Lines 30-34

The bowsprit, the arrow, the longing, the lunging heart—

(…)

doesn’t injure the sand. There are so many islands!

The bowsprit (the forward-pointing beam at the front of a ship) is likened to an arrow through an implied metaphor, creating an image of motion, pursuit, and targeting. However, the focus shifts from the physical object to the emotional: the “lunging heart”. By blending object and emotion, the speaker turns the schooner’s journey into a metaphor for human longing. The intimacy of this is heightened through the personification of the heart.

The list form, ending in an em dash, leaves the thought hanging, as if gasping for breath, or reaching. The ‘l’ alliterates used in line 30 reinforce the impression of a forward thrust, as the boat progresses forward as an arrow. Its aim is accurate and determined.

Line 32 introduces a paradox: a target implies purposeful aim and direction, but “we’ll never know” undermines that sense of predetermination. Finding that singular place of comfort, peace, and clarity is a “vain search” for a non-existent utopia. The personified “island that heals with its harbor” and “guiltless horizon” suggest a world free of flaws – whether colonial legacy, political trauma, or Shabine’s complicated mixed-race ancestry.

“[W]here the almond’s shadow / doesn’t injure the sand” is evocative imagery describing a world where no harm exists, and further points out the absurdity of longing for such a utopia. With the exclamation, “There are so many islands!” the speaker both affirms abundance and acknowledges the impossibility of the search. As an archipelago, the Caribbean is fragmented in nature, and so is its identity. Thus, there can be no perfect home or easy answers; each one has its particular cocktail of beauties and banes. Walcott’s assertion is pragmatic: we are better served making sense of and reconciling with the world we have than wishing for a fantastical one.

Lines 35-40

As many islands as the stars at night

(…)

island in archipelago’s of stars.

In line 35, a simile likens islands in the sea to stars in the night sky, doubling up on the nautical imagery. As one would navigate to these islands, they would be using the stars for guidance. A parallel is established between the two realms, reinforcing the endless opportunities that await Shabine.

A metaphor casts the universe as a “branched tree” from which “meteors” are shaken like ripe fruit, evoking a living network of connections between the islands. In a giddy, epiphanic state, Shabine sees the starry sky as a mirror of the scattered islands below, from where lights would shine from windows at night, and declares that the stars are “islands,” and the Earth “one island in archipelagoes of stars.”

“Venus” and “Mars” are examples of double entendre, as they refer to the planets, but also allude to the Roman deities by the same names. The two heavenly bodies are juxtaposed through visual parallelism and anaphora, creating a clear dichotomy between the two. Venus, emblem of love and beauty, and Mars, of war and conflict, are opposites whose “fall” into oneness. This reflects a deeper, natural synthesis at work in the cosmos. Fricative alliteration, seen in words like “from”, “falling”, “fruit”, “[f]light”, and “fall”, creates a soft, hushed descent; together with the repetition of “fall”, it deepens the sense of inevitability of this process.

Linking this to the idea of a multitude of distinct islands explored in the last section, this section suggests a perfection in the cosmic interconnectivity of the islands. Line 40 expands Shabine’s vision: Earth, the cradle of all human striving, is only a small point in an immense, glittering sea of stars. With this awareness, he loosens his grip on grand demands, easing into acceptance of the world and himself within it.

Lines 41-50

My first friend was the sea. Now, is my last.

I stop talking now. I work, then I read,

cotching under a lantern hooked to the mast.

(…)

“My first friend was the sea,” personifies the sea, accompanied by fricative alliteration and sibilant consonance. Together with “Now, is my last,” it presents us with a cycle typical of Walcott’s poetry. This hints that, as one born in the Caribbean, Shabine has a close relationship with the surrounding ocean, and his flight away leads him back to his origin. As if to emphasize this return, from this point to the end, he speaks more in Creole, like one who resumes speaking in his mother tongue when he comes back from exile.

The first part of this thematic section is fragmented and choppy, suggesting an unharmonious relationship with the sea. Rather than a romantic idealized flight that promises happily ever after, Shabine has moments when he is forced to grapple with real sadness as the outcome of abandoning all he had held dear. Line 42 shows Shabine trying to distract himself from painful memories by focusing on work, reading, or staring at the stars. Notably, these actions seem like busy distractions; this is Shabine at odds with nature.

However, the second part introduced by “[s]ometimes is just me” marks a volta, showing him free of anxiety, at one with nature. Its flow is fluid, rendered in beautiful imagery that suggests that he feels at home with the sea. Associating the waves with their softly cutting movement in “soft-scissored foam” – note also the sibilant consonance – creates a vivid image of the calm waves. In this simile, “the moon opens a cloud like a door,” the moon is personified as one peering. Line 50 drives this point home in an apostrophe that has Shabine singing “from the depths of the sea.”

“[R]oad in white moonlight” is a metaphorical light guiding Shabine toward a final destination or a sense of peace, a “home,” that is not a physical house but a feeling of belonging. This implies a spiritual homecoming rather than an actual one through his voyage; even if Shabine eventually returns to his actual home, he returns fully at home with himself.

FAQs

The narrator is Shabine, a fictional mixed-race seaman from St. Lucia and the central persona of Derek Walcott’s ‘The Schooner Flight: 11: After the Storm‘. A poet and outcast, he flees his homeland aboard the schooner Flight to escape personal betrayal and the constraints of island life. Through Shabine’s voice, Walcott blends autobiography and invention to explore themes of identity, exile, and the search for a spiritual home in the Caribbean, making him both a vivid character and a vessel for the poem’s larger meditations.

The storm represents a period of chaos and suffering in Shabine’s life, likely a metaphor for his troubled relationships and feelings of guilt. ‘After the Storm‘ signifies a moment of clarity and peace. As the sea calms, Shabine finds spiritual reconciliation with his past and a renewed sense of purpose. This shift from chaos to calm reflects his internal journey from turmoil to acceptance.

The name Shabine is crucial because it’s a Caribbean Creole term for a person of mixed race, particularly one with light skin, and it carries a sense of being culturally and racially in-between. This identity is central to the narrator’s character. His mixed heritage makes him feel like an outcast, not fully belonging to any one group or place. This feeling of rootlessness is the primary motivation for his journey on the schooner Flight, as he seeks a place where he can finally find a sense of belonging and a “guiltless horizon”: a sort of blank slate home ground.

The final message is one of acceptance and quiet solitude. Shabine realizes that his journey isn’t about finding a physical destination but about achieving inner peace. He stops talking, accepting that his true home is in the simple solitude of the sea and the stars. His final words, “Shabine sang to you from the depths of the sea”, suggest that his poetry and voice have become one with the ocean, finding a timeless and universal expression.